As the credit crisis grinds on, the prospects for a quick recovery darken

by David Henry and Matthew Goldstein of BusinessWeek

It has been a year since the global credit markets first seized up, and four months since the dismantling of Bear Stearns. Yet bad things keep happening, from the failure of IndyMac and the stock routs of Lehman Brothers (LEH) and others to the market’s collective yawn at the Treasury Dept.’s plan to bolster mortgage giants Fannie Mae (FNM) and Freddie Mac (FRE). Once again, the optimists who thought the crisis was over have been proven wrong. “People underestimated how bad things were last summer,” says Frank Partnoy, a former Wall Street derivatives trader turned professor at the University of San Diego Law School.

Did they ever. July’s rat-a-tat-tat of dismal news suggests that the scope of the credit crunch is much broader than most people thought. Traders, investors, bankers, and economists are waking up to the possibility that Wall Street’s recovery from the worst financial disaster since the Great Depression could grind on for years. And they’re realizing that while the debacle was of Wall Street’s making, its aftermath will weigh on banks, other companies, and consumers alike.

One thing is for sure: The new normal won’t be as fun as the recent past. Banks will be smaller and fewer. Capital will be harder to get for some consumers and companies. And more of that capital will be parceled out by lightly regulated hedge funds and private equity firms, for better or worse, as the balance of power on Wall Street shifts.

Why hasn’t the healing begun? The answer lies in the mechanics of leverage, or borrowed money, which banks not only provide to customers but also use themselves. Leverage is a powerful but dangerous tool, intoxicating on the way up and devastating on the way down. Banks live on the stuff: When they post profits, they borrow more money to make more loans and book still more profits. During the boom, bigger mortgage loans pumped up home prices until people couldn’t handle the debt and the bubble burst. Then the banks, poorer from the losses, had to cut back their own borrowing, too. Now the damage is spreading. How far? Simplified, for every dollar of bank wealth lost, government-regulated commercial banks must eliminate some $10 of lending; for investment banks, the figure can be $30.

The extent of the credit contraction to come will depend on the banks’ initial losses—an elusive figure, to be sure, and one that keeps growing. The latest loss tally is $400 billion across the credit markets, but the International Monetary Fund says the total could swell to $1 trillion. Slap on a leverage multiplier of 10 or 15, and the math turns grim. “I believe we will live in a deleveraged state until the next generation of management gets in place and doesn’t remember what we went through here,” says Robert Greifeld, CEO of Nasdaq (NDAQ). “The harder question is about the lack of leverage in the broader economy: How does it ripple through?”

“Fearful of Losses”

It’s tempting to view the July swoon as a sign that a bottom is near. Sure, the U.S. stock market seems to be nearing a trough and could rally soon, as it did on July 16. Then again, in protracted downturns the first several waves of bottom-fishers are usually wiped out. Witness the pain suffered by many of the professional investors who have bet on beaten-down financials in the past year.

More important, the stock market and the credit markets are rarely in perfect sync. In the credit market, history shows that “even after things hit bottom, there is a slow, long recovery,” says Todd A. Knoop, economics professor at Cornell College and author of a textbook on the impact of financial-system swings on the economy. Earlier in the decade, credit markets remained weak after the stock market began a sharp recovery. Says Richard Sylla, professor of economics and financial history at New York University: “A couple hundred years of financial history show that whenever you have a financial crisis like this, banks don’t like to lend.”

The next few years promise to be especially rough, judging from the numbers so far. Banks cut back on credit in the three months through mid-June at a 9% annualized rate, the worst contraction in 35 years of data, according to Leigh Skene of Lombard Street Research. Issuance of mortgage-backed securities and corporate junk bonds this year is down 87% and 63%, respectively, according to research firm Dealogic.

A recent study projected that losses resulting just from mortgage-related lending would sap $1 trillion of credit from the U.S. economy. Banks “have to shrink,” says the University of Chicago’s Anil K. Kashyap, one of the authors.

Even if banks were able to rush back into heavy leverage soon, investors likely wouldn’t stand for it. “On the way up, banks get penalized [by stock investors] for not being aggressive enough,” says Martin Fridson, CEO of money manager Fridson Investment Advisors. “On the way down, the pressure is on to show how conservative you are. If lenders are fearful of losses, they are going to contract.”

The Endangered Banks Lists

Regulators could add fuel to the deleveraging machine with tougher rules. Already, Swiss bank regulators want to tighten standards following big losses at UBS (UBS) . The Federal Reserve, in return for opening its discount window to investment banks, will likely limit the amount of leverage those banks can use. “If new regulation occurs, the next [credit] cycle could be muted,” warns David Trone, a senior analyst with Fox-Pitt Kelton Cochran Caronia Waller.

But regulators are in a bind. They don’t want to see more bad lending, but they also don’t want to cut off credit for an economy that needs it. Consider the pending legislation and new regulation to revive the housing market and support Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Along with measures to keep borrowers out of foreclosure, they include provisions that ambitiously try to bar bad lending without discouraging the good. Balancing safety concerns and growth aspirations is a delicate dance indeed.

Outright government takeovers of banks, such as the July 11 seizure of IndyMac, pose another not-so-obvious threat to lending. Takeovers can save money in the long run and are almost always necessary to prevent widespread panic. But they constrain lending, too. When banks are taken over by the government, their shareholders usually register losses. Bank capital is erased from the financial system, and with it, the ability to make new loans. Moreover, lending practices are certain to be more conservative under Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. management than in the past.

More bank failures and seizures are likely. The FDIC says its list of problem banks is up to 90 now, nearly twice as many as two years ago. Treasury has its own list of 100 banks in danger, say people familiar with the matter. The lists haven’t been made public, but investors on Wall Street are making their own judgments. In recent days, shares of Washington Mutual (WM), National City (NCC), Wachovia (WB), Sovereign Bancorp (SOV), Colonial BancGroup (CNB), and Zions Bancorp (ZION) have been whipsawed.

Systemic Problem

Predicting the direction of global markets is a fool’s game. There’s no telling what major upheavals, positive or negative, could be in store. (In the dark days of 1992, how many people were heartened by the promise of the Internet?) To be sure, Wall Street is already busy dreaming up new instruments that could, in theory, restore leverage to the system and pump up asset values again. Even if it doesn’t, time is a great healer of credit-market wounds.

The question is how long it will take for these wounds to heal. Milton Ezrati, senior economist and market strategist at fund manager Lord Abbett, is convinced that “the worst is over.” The interest rate cutting and other Fed actions that started last September should give the economy a boost soon, he says. But he’s careful to warn that another credit boom isn’t in the offing.

Others offer less optimistic scenarios. Charles Geisst, professor of finance at Manhattan College and author of several books on financial crises, says the country is in the early days of the worst “capital strike” by banks since the one that raged from the Great Depression to the 1950s. He allows this one won’t be as bad, but adds: “The problem is a systemic one that has dragged everyone down.”

New York University’s Sylla sees parallels to the last big credit crisis in the U.S., which started in 1989 with the collapse of the junk bond market. Tighter credit weighed on the economy for at least three years, thwarting President George H.W. Bush’s reelection bid, he says. By 1994 normalcy had been restored to the credit market, but it took until the late 1990s for boom psychology to return. Sylla worries that the pain from the current crunch will last even longer. “Many historical financial crises, a year later, were pretty much over,” he says. “There’s nothing about this one that looks like it is really over yet.”

Fewer, Smaller Players

Indeed, banks’ best opportunity to reverse the credit crunch quickly&with capital infusions&is vanishing. Everyone remembers Saudi Prince Alwaleed bin Talal’s big investment in Citibank (C) in the early 1990s, when it was on the brink of collapse. The stock subsequently soared. Some investors no doubt want to repeat that feat now. But so far, many of the bets by sovereign wealth funds and private equity firms haven’t paid off. TPG, formerly known as Texas Pacific Group, led an investor group that paid $7 billion for a stake in Washington Mutual in April. The stock has since dropped by 60%. Given the losses they’ve suffered, investors could be unwilling to make more bets.

It could take years for some banks to complete the painful deleveraging process on their own. They’ll sell off healthy assets whenever possible and try to partner up with rivals to cut costs. Some will die. David A. Hendler, an analyst at debt-research firm CreditSights, says Wall Street may be entering an era in which there are fewer investment banks and those that exist aren’t as important.

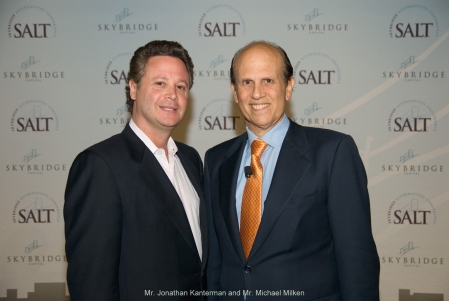

That will open the door to competition from hedge funds and private equity firms. Of course, the deleveraging hangover means they won’t be able to shower companies with loans anytime soon. But some private investment pools are beginning to connect companies seeking capital with investors providing it—just as investment banks do. “The Wall Street banks in general are going to lose market share,” predicts Jonathan Kanterman, managing director with money manager Stillwater Capital Partners.

Creating More Problems

The growing market for private placements, for example, is enabling more corporations to sidestep Wall Street stock underwriters and go directly to hedge funds, pension funds, and other big investors to raise cash. Last year private equity giant Kohlberg Kravis Roberts set up its own team to find institutional buyers for large equity stakes in companies it had taken private. Historically, that’s been a job handled by Wall Street. With that team in place, there’s nothing to stop KKR from offering its services to other private companies looking to place stock.

Hedge funds and private equity firms also have become big providers of so-called mezzanine financing, a type of loan that can be converted into an equity stake in a company. Some of the new players may even try to coax life out of the moribund securitization market over time. Chicago-based hedge fund Citadel Investment Group, for example, recently hired a top JPMorgan Chase (JPM) executive to head its new “securitized products” group.

But a landgrab by big hedge funds and private equity firms might create new problems. The Securities & Exchange Commission and the Finance Industry Regulatory Authority oversee investment banks to some degree, and the Federal Reserve is moving in that direction. But hedge funds are largely unregulated and aren’t bound to make any disclosures to anyone but their investors. Even that information is often incomplete. A move by hedge funds into traditional corporate finance would mean even less transparency than exists on Wall Street now. “It’s just a swing from one problem to another,” says Manhattan College’s Geisst.

Lehman’s Pain

To see just how stuck in the mud Wall Street is, one need look no further than Lehman. Investors have abandoned the firm in droves on fears of a sudden collapse and the expectation that it will be swallowed up by a larger rival—perhaps Goldman Sachs (GS)—at a bargain price. With shares trading around $16, down 74% for the year, Lehman sports a market value of just under $12 billion.

Lehman has been in full deleveraging mode of late. Its leverage ratio now stands at 24 (through May), down from 31 two quarters earlier. Its mortgage business has all but dried up: Over the six months ended in May, the firm originated just $2 billion in residential mortgages, compared with $32 billion during the same period in 2007, and $4 billion in commercial mortgages, down from $32 billion. “They bought risky securities and they levered up, but the bet didn’t pay off,” says Brad Golding, a portfolio manager with money manager Christofferson, Robb & Co., who has no position in Lehman’s stock. “There’s no difference between Lehman and a subprime borrower who bought more house than he could afford.”

Much of Wall Street did the same, leveraging up to finance mortgages that could be later repackaged into securities and sold to investors. Just about all of the $48 billion in so-called collateralized debt obligations Merrill Lynch (MER) underwrote in 2007 are either in default or on the verge. Now its chief executive, John A. Thain, is being forced to explore selling off pieces of its choicest assets to fill the gaping balance-sheet holes created by Merrill’s bad business decisions. Says derivatives consultant Janet Tavakoli: “They really did create their own problems.”

By setting up the housing bust, Wall Street has created problems for the rest of us, too. The real estate meltdown has left consumers vulnerable to soaring gas prices, which are only worsening home foreclosures and bank losses. That’s leading to still-more deleveraging and even tighter credit. It’s a vicious cycle, and it won’t reverse easily.

Henry is a senior writer at BusinessWeek. Goldstein is a senior writer at BusinessWeek.

http://www.businessweek.com/print/magazine/content/08_30/b4093023467572.htm